Tiny Mitochondria Are Mighty

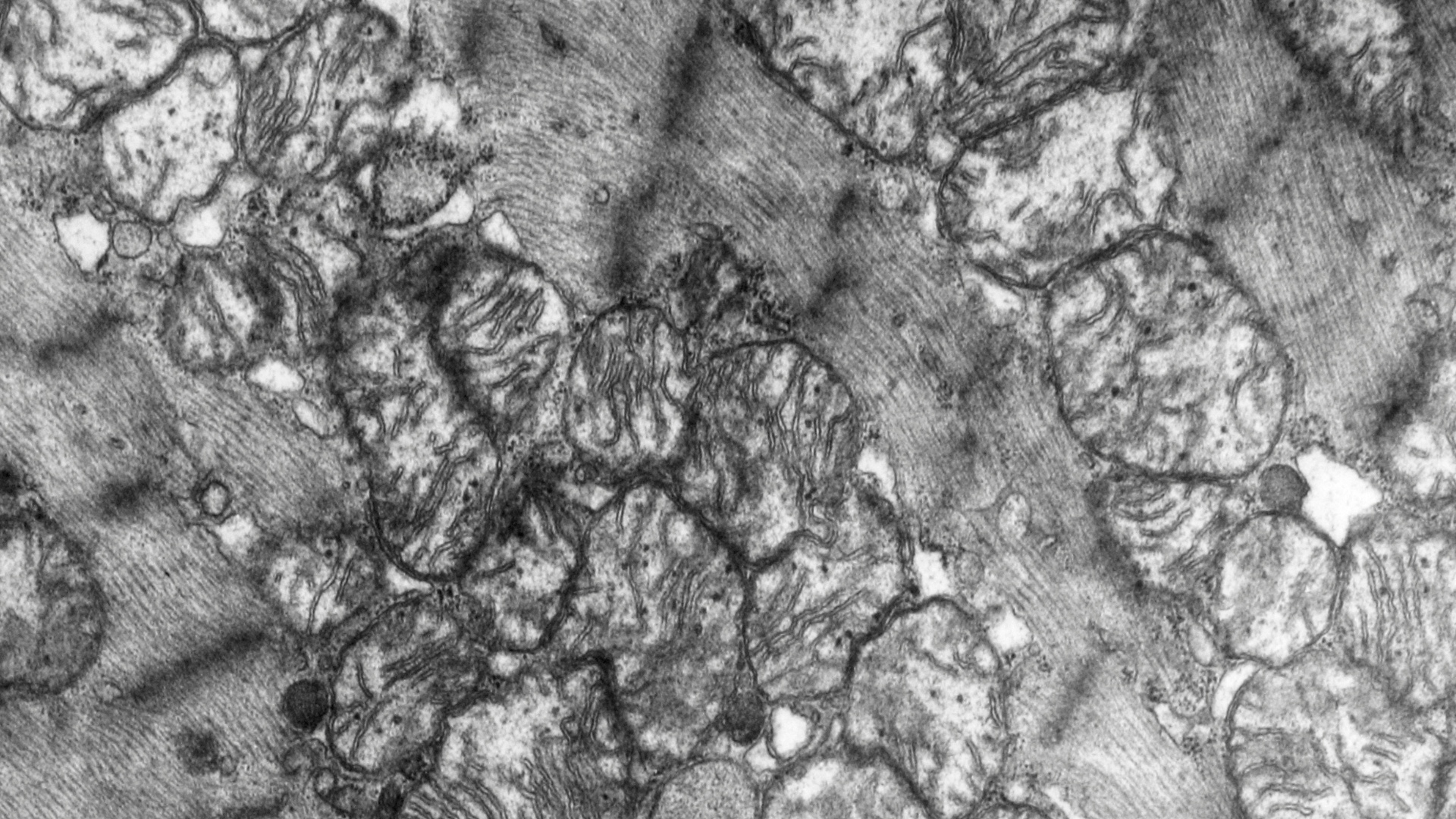

Our mighty mitochondria perform some of the most amazing aspects of health because of their ability to convert food into energy. Mitochondria are tiny, microscopic “organelles” (essentially ancient bacterium passed down from mother to child that have their own DNA, different from ours) that populate nearly every cell of our body, red blood cells being a notable exception. Their functions are critical for achieving and maintaining a well-regulated body equipped with enough energy to not only survive but to really thrive.

Mitochondria are primarily responsible for the conversion of the food we eat – carbohydrates, fats and proteins – into our body’s main energy currency, ATP (adenosine triphosphate). ATP is the fuel that makes our bodies function. The number of mitochondria that inhabit any given cell in our body depends on that cell’s energy needs. For example, there may be 1,000-2,000 mitochondria in each individual liver cell, or 5,000-8,000 in just one heart cell, or 2 million in brain cells (neurons).

The ATP molecule is created through a process called cellular respiration that allows it to carry, store and release energy to cells in need. When mitochondria are compromised, this process is distorted at a cellular level: the very tissues that make up critical organs are less capable of producing and utilizing ATP, and they lose functionality.

Life-Generating Mitochondria

Because of their ability to generate energy, mitochondria play a significant role in the lives of cells throughout the body systems:

- Mitochondria help the neurovascular system by:

- Supporting cognitive and neurological development

- Supporting calcium signaling for nerves and muscles

- Regulating the production of neurotransmitters such as catecholamines used in the “fight or flight” response

- Regulating excitotoxicity by balancing GABA and glutamate

- Mitochondria support tissue growth and repair:

- Helping to regulate cell growth and development

- Invoking apoptosis (cell death) to get rid of unwanted (senescent) cells

- Mitochondria enable the immune system by:

- Responding to adversity (e.g., pathogenic viruses, bacteria etc.)

- Mitochondria allow the endocrine system by:

- Maintaining appropriate body temperature and homeostasis

- Regulating stress hormones such as cortisol and

- Regulating reproductive hormones such as estrogen, progesterone and testosterone

- Mitochondria complement detoxification/waste removal systems by:

- Supporting the high energy demands of the emunctories (routes of elimination) such as the gastrointestinal tract, liver, kidneys, lymphatics, skin, lungs and uterus

Given this small sample of their roles, it is no surprise that mitochondria are often called the “powerhouse of cells” or “the master regulators”.

Mitochondria, Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Free Radicals

As with manmade power plants, mitochondria also produce potentially harmful “waste” – byproducts called free radicals that are extremely reactive. These highly volatile molecules need to be removed, recycled or mitigated in some way by the body. When the total load of stressors on a body is too great or the demands on the mitochondria outweigh their capacity to deliver, these byproducts may be left “unchecked” and accumulate beyond the body’s capacity to manage them effectively. A subset of free radicals, called reactive oxygen species can cause significant damage to DNA, protein, and other cellular components.

When the body encounters too many stressors in any form, such as a high total load, the number of free radicals rises exponentially, leading to more oxidative stress which triggers an inflammatory response, which leads to more oxidative stress, which can compromise the body’s biological systems, cells, tissues and organs and harm the mitochondria itself. This vicious cycle further damages cells, proteins and DNA and contributes to many chronic conditions and diseases.

If antioxidants – molecules in the body that help mitigate oxidative stress which can be found in many fruits, vegetables, and supplements – are not sufficient to meet the body’s demands, oxidative stress overtakes the body’s defenses and leads to oxidative damage of whole systems. For example, even a very small change in mitochondrial function can have a profound impact on brain, muscle and heart functioning.

Signs and Symptoms of Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Medical practitioners may suspect mitochondrial dysfunction when there are a collection of signs and symptoms from the following list of examples (roughly grouped into three categories):

Neuromuscular and/or Developmental Issues

- Low muscle tone (hypotonia)

- Difficulty swallowing or feeding

- Muscle wasting

- Headaches

- Fainting

- Seizures

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Parkinson’s disease

- Fibromyalgia

Constitutional Problems and/or Chronic Health Conditions

- Low stamina

- Slow metabolism

- Low energy

- Chronic fatigue

- Cancer

- Chronic inflammation

- Accelerated aging

- Cardiovascular disease

- Insulin resistance

- Metabolic syndrome

- Diabetes

- Obesity

- Nutrient deficiencies

- Chronic and/or recurring infections

Other Signs and Symptoms Related to Specific Body Systems

- Diarrhea

- Constipation

- Acid reflux

- Unexplained vomiting

- Ischemia

- Atherosclerosis

- Respiratory problems

A Deeper Look at Hypotonia and Muscle Tone

Enough can’t be said about how important mitochondria are to muscle function. Mitochondria are essential for muscle tone, growth and development. When mitochondria are unable to produce enough energy inside muscle cells, muscle weakness and hypotonia may present. Children with low muscle tone are often described as having hypotonia. When babies experience muscle weakness, it may affect their ability to feed. Babies with feeding difficulties may be experiencing mitochondrial dysfunction in addition to other challenges such as tongue tie. Hypotonia or mitochondrial challenges are common in conditions such as Down Syndrome, Prader-Willi, muscular dystrophy and cerebral palsy.

Muscles require a huge amount of constant energy to maintain strength and function; otherwise, they can become floppy and weak. Children with mitochondrial disorders exhibit low muscle tone in many forms such as an inability to sit, stand or walk, or in their ability to hold pencils, write by hand, draw pictures, tie shoelaces or button shirts.

It’s important to understand the vital role of mitochondria to address a child’s health. Improving a child’s muscle tone (with multiple supports, including nutrition and targeted supplements, discussed below) can help with a variety of conditions and may help children meet their developmental milestones.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Autism

Mitochondrial dysfunction clearly impacts many of the body’s energy systems in children with autism. Highly impacted areas tend to be neurologic (not just the brain, but also systems such as the autonomic, enteric, and central nervous systems), cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal. Lack of ATP can contribute to many of these issues seen in autism:

- Developmental delays or disabilities

- Strokes

- Vision impairment

- Language impairment

- Slow growth

- Fatigue

- Movement disorders

- Diabetes

- Heart/liver/kidney conditions

- Respiratory conditions

- Gastrointestinal conditions

- Auditory processing

- Motor planning

- Cognitive skills

- Social skills

- Seizures

When there is not enough ATP, children with autism may present with normal muscle tone in the lower extremities of their bodies but lack sufficient muscle tone in the upper parts of their bodies. If this is the case, they may lack fine-motor skills needed for speech.

More About Speech

Parents are usually extremely concerned when their children are non-speaking or have limited language. Lack of speech and language are very emotional topics, and as we know, the inability to communicate can have a debilitating effect on a child’s development and quality of life. There may be different biochemical reasons for speech delays in a child; it is valuable to investigate nutritional and other root causes, too.

An important piece of speech and language that is often overlooked is the role of the mitochondria and its respiratory complexes – the steps it takes to make ATP. You might already have guessed what speech and language have to do with mitochondria: muscle tone. A common issue for children with autism is that their bodies lack the energy to create enough muscle tone for them to develop and support a speaking voice.

As with their muscles, children’s brains require an enormous amount of energy, especially at a young age when the brain is still developing. Inadequate cellular energy affects how the brain cells connect and “talk” to one another and our ability to talk– period – communication is impacted on many levels.

More About Speech and Respiratory Complexes

Respiratory complexes are a crucial part of mitochondria. They make up an electron transport chain (or sequence of enzymatic steps needed to make ATP) that consists of four major protein complexes I, II, III and IV.

Children with neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism often have defects in respiratory complexes II and III, impacting the production of ATP. Low energy, in turn, can affect how brain cells connect and communicate impeding a child’s developmental milestones. For example, an important area of the brain needed for speech is called Broca’s area. It requires huge amounts of energy. Children who have impairment with complexes II and III manifest problems in delayed speech, poor motor coordination and reduced cognitive processing.

Testing and Nutritional Supplementation

Two important tests to determine underlying mitochondria issues or needs are the MitoSwab by Religen Diagnostics and the Organic Acid Test (OAT). Both tests can help medical providers pinpoint the source of signs and symptoms associated with mitochondrial dysfunction.

Another valuable test checks for antibodies to the brain’s folate receptors in a blood sample. It is called the FRAT (Folate Receptor Antibody). If these antibodies are present, they can interfere with speech production and could also suggest the need to avoid dairy.

The following nutrients are often used to support healthy mitochondria; a root-cause-oriented medical provider will likely develop a custom mitochondrial cocktail from these nutrients based on a child’s lab test results and bio-individual needs:

- Phospholipids such as phosphatidylcholine

- Fatty acids such as omega-3

- Minerals such as magnesium

- CoQ10 (ubiquinol)

- Glutathione

- Acetyl L-carnitine

- Vitamin B complexes usually consisting of methylated B vitamins

- Superoxide Dismutase (SOD)

- D-ribose

- NADH (Co-Enzyme 1)

- PQQ Pyrroloquinoline Quinone

- Alpha Lipoic Acid (ALA)

- N-Acetyl Cysteine (NAC)

- Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)

- Polyphenols

Supporting Mitochondria through Daily Activities

Before jumping into the many things that can harm mitochondria, here is a review of some approaches that have been shown to support them. The following are examples of ways to help facilitate optimum functioning:

- Daily exercising

- Weight-bearing exercise

- Autophagy from intermittent fasting

- Nutritional supplementation

- Near-infrared light

A Special Look at the Need for L-Carnitine

L-carnitine is an extremely important element of protein from our diets needed by mitochondria to create energy. It is an amino acid that is necessary to transport long-chain fatty acids across the inner membrane into mitochondria, where they are broken down and the fatty acids are turned into ATP energy. Fatty acids are unable to get into the mitochondria without L-carnitine.

Most people acquire L-carnitine through diet such as red meat (the best source), poultry, fish and dairy products. A carnitine deficiency in infancy or childhood, however, could show symptoms such as:

- Severe brain dysfunction or encephalopathy

- A weakened and enlarged heart (cardiomyopathy)

- Vomiting

- Muscle weakness

- Low blood sugar

L-carnitine also prevents toxic build-up in the mitochondria and in so doing supports overall cellular health. It is also involved in more than 100 enzymatic reactions including those used in these processes:

- The citric acid cycle

- Maintaining a Coenzyme A balance to create ATP

- Reducing oxidative stress

- Protecting the mitochondrial membranes from damage

- Breaking down fatty acids into ATP

We can see why there cannot be a discussion about mitochondria without stressing the importance and necessity of L-carnitine.

What Is Toxic to Mitochondria?

Unfortunately, today we are surrounded by stressors and toxins that damage mitochondria. Many diet, lifestyle and environmental factors, play a part in contributing to our mitochondria’s total load, including:

- Artificial environments full of WiFi radiation and other EMFs

- Lack of nutritious foods or too many processed foods and food dyes

- Poor quality fats (including oxidized oils) or low intake of high-quality fats

- GMO foods, especially those treated with pesticides/glyphosate

- Pathogens or an imbalanced microbiome (known as gut dysbiosis)

- Low sun exposure, poor air quality, or exposure to fluorescent light

- Artificial blue light from screens or lack of natural infrared light

- Chronic circadian misalignment – being out of rhythm with nature

What Is Happening at a Cellular Level?

As a physician-scientist, Robert Naviaux’s groundbreaking research proposed that mitochondria respond to these toxic stressors as a threat. He called this the “Cell Danger Response” (CDR). In 2013, Dr. Naviaux published a paper about CDR as a theory about autism showing that he was able to reverse behaviors and biochemical abnormalities of autism in mouse models. He later published studies about how a 100-year-old drug called suramin to lower that danger signal. Dr. Naviaux feels much work needs to be done to perfect his solution, but he remains certain on this thought:

“Autism has taught me that if the Cell Danger Response remains on, then healing, or the return to normal child development, is blocked. If we unblock healing by turning down the CDR, then dramatic improvements can occur. I believe autism is the key to understanding over half of all chronic disease, in children and adults alike.”

According to Doug C. Wallace, a geneticist and evolutionary biologist, today’s environmental toxicity accelerates oxidative stress to create more dysfunctional mitochondria.

“Virtually all the common diseases of aging – diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s are all linked to mitochondrial dysfunction, not inherited nuclear DNA mutations.”

Dr. Wallace also maintains that “Disease is a bioenergetic collapse, not a genetic destiny.” In other words, “disease” is the energetic downfall which causes the collapse of mitochondria rather than genetic etiology. The focus should be on the restoration of mitochondria, not on “bad genes”.

Both conventional and integrative practitioners, from psychiatrists to pediatricians to neurologists, are beginning to focus on mitochondria as a key issue for better understanding where/how health problems arise and how to address them. This is very significant progress for all health arenas and stages of life. These practitioners are helping their patients by getting to their root causes, not just addressing patient symptoms.

Conclusion

If you are raising children, it is valuable to consider the health of their mitochondria and to make sure they are getting enough protein, healthy fats and other nutrients described above to support their mitochondria. It is also important to lower their total load of stressors. If you also “lack energy” or are one of those people categorized as having a “slow metabolism,” you can potentially increase your metabolism by supporting your own mitochondria. If you do nothing else new for you or your child’s body, consider supporting the mitochondria! These organelles are a gateway to life and key to all bodily functions that require energy. They truly do allow us to survive and thrive. This is why they deserve the title “mighty mitochondria”.

About Heather Tallman Ruhm MD

Heather Tallman Ruhm MD is the Medical Director of the Documenting Hope Project. She is a Board Certified Family Physician whose primary focus is whole-person health and patient education. She draws on her conventional western training along with insights and skills from functional, integrative, bioregulatory and energy medicine. She believes in the healing capacities of the human frame and supports the power of self-regulation to help her patients recover and access vitality.

About Teresa Badillo

In the 1980s she worked overseas in Rome, Italy at the Japanese Embassy in the office of the United Nations (FAO) as a speech writer. She also began her long journey in alternative healing while living in Rome.

After moving to New York and while raising her family of seven children, Teresa embarked on a mission to find alternative non-invasive biomedical, therapeutic, sensory and educational solutions for autism after the diagnosis of her son in the early 1990s.

She won a court case in 1995 against the Rockland County School District in New York to enable ARC Prime Time for Kids to be the first school using Applied Behavioral Analysis teaching method for autism that was paid for by the Rockland County School District. The following year she was instrumental in getting the New York Minister of Education to approve an extension of the ARC license from 5 to 21 years.

She has worked over the years in a number of alternative medical practices with doctors and practitioners organizing various biomedical intervention options for children with autism. Since the mid 1990s, Teresa has served on several boards:

- Foundation for Children with Developmental Disabilities

- The Autoimmunity Project

- Developmental Delayed Resources

- Epidemic Answers

She continues to consult and advise parents on all different areas of autism especially nutritional protocols. Since 2006 she has worked with NutraOrgana, LLC and BioCellular Analysis Testing. She currently researches, writes the newsletter and blogs Teresa’s Corner for The Autism Exchange (AEX). She also writes blog posts and pages for Documenting Hope.

Still Looking for Answers?

Visit the Documenting Hope Practitioner Directory to find a practitioner near you.

Join us inside our online membership community for parents, Healing Together, where you’ll find even more healing resources, expert guidance, and a community to support you every step of your child’s healing journey.

Sources & References

Andreazza, A.C., et al. Mitochondrial complex I activity and oxidative damage to mitochondrial proteins in the prefrontal cortex of patients with bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010 Apr;67(4):360-8.

Balcells, Cristy. Autism & Mitochondrial Disorders: How Much Do We Really Know?. MitoAction.org. 29 Jan 2009

Beal, M.F., et al. Therapeutic approaches to mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009 Dec;15 Suppl 3:S189-94.

Bradford, B.L., et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Type 2 Diabetes. Science. 2005 Jan 21;307(5708):384-7.

Bradstreet, J.J., et al. Biomarker-guided interventions of clinically relevant conditions associated with autism spectrum disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Altern Med Rev. 2010 Apr;15(1):15-32.

Burchell, V.S., et al. Targeting mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative disease: Part I. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2010 Apr;14(4):369-85.

Burchell, V.S., et al. Targeting mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative disease: Part II. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2010 May;14(5):497-511.

Davi, Alyssa. Has Your Child with Autistic Symptoms Been Properly Screened for a Subset of Mitochondrial Disease Known as OXPHOS?...Probably Not. Autism File. 2010; 36.

Dehley, Leanna M., et al. The Effect of Mitochondrial Supplements on Mitochondrial Activity in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Clin Med. 2017 Feb; 6(2): 18.

Ferrer, et al. Early involvement of the cerebral cortex in Parkinson's disease: convergence of multiple metabolic defects. Prog Neurobiol. 2009 Jun;88(2):89-103.

Filipek, P.A., et al. Relative carnitine deficiency in autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2004 Dec;34(6):615-23.

Haas, R.H., et al. Mitochondrial disease: a practical approach for primary care physicians. Pediatrics. 2007 Dec;120(6):1326-33.

Hao, J., et al. Mitochondrial nutrients improve immune dysfunction in the type 2 diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats. J Cell Mol Med. 2009 Apr;13(4):701-11.

Herbert, M.R. Contributions of the environment and environmentally vulnerable physiology to autism spectrum disorders. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010 Apr;23(2):103-10

James, S.J., et al. Cellular and mitochondrial glutathione redox imbalance in lymphoblastoid cells derived from children with autism. FASEB J. 2009 Aug;23(8):2374-83.

Kato, T. The role of mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder. Drug News Perspect. 2006 Dec;19(10):597-602.

Kelley, R.I. Evaluation and Treatment of Patients with Autism and Mitochondrial Disease. Kennedy Krieger Institute, Division of Metabolism.

Klehm, M., et al. Clinician's Guide to the Management of Mitochondrial Disease: A Manual for Primary Care Providers. MitiAction.org. 2014.

Konradi, C., et al. Molecular evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004 Mar;61(3):300-8.

Korson, M. Mitochondrial Disease and Patient Challenges. MitoAction. 2008.

Leib, S., et al. Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation (OXPHOS) Dysfunction: A Newly Emerging Category of Autistic Spectrum Disorder Information for Primary Care Physicians. MitoAction.org. 2010.

Li, L., et al. Molecular pathways of mitochondrial dysfunctions: possible cause of cell death in anesthesia-induced developmental neurotoxicity. Brain Res Bull. 2015 Jan:110:14-9.

Liu, J. The effects and mechanisms of mitochondrial nutrient alpha-lipoic acid on improving age-associated mitochondrial and cognitive dysfunction: an overview. Neurochem Res. 2008 Jan;33(1):194-203.

Liu, Q., et al. Organochloride pesticides impaired mitochondrial function in hepatocytes and aggravated disorders of fatty acid metabolism. Sci Rep. 2017 Apr 11:7:46339.

Long, J., et al. Mitochondrial decay in the of old rats: ameliorating effect of alpha-lipoic acid and acetyl-L-carnitine. Neurochem Res. 2009 Apr;34(4):755-63.

Mabalirajan, U., et al. Effects of vitamin E on mitochondrial and asthma features in an experimental allergic murine model. J Appl Physiol. 2009 Oct;107(4):1285-92.

Maes, M., et al. Coenzyme Q10 deficiency in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) is related to fatigue, autonomic and neurocognitive symptoms and is another risk factor explaining the early mortality in ME/CFS due to cardiovascular disorder. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2009;30(4):470-6.

Maes, M., et al. Lower plasma Coenzyme Q10 in depression: a marker for treatment resistance and chronic fatigue in depression and a risk factor to cardiovascular disorder in that illness. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2009;30(4):462-9.

Miller, M., et al. Do antibiotics cause mitochondrial and immune cell dysfunction? A literature review. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2022 Apr 27;77(5):1218-1227.

Morino, K., et al. Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance in humans and their potential links with mitochondrial dysfunction. Diabetes. 2006 Dec;55 Suppl 2:S9-S15.

Napoli, E., et al. Toxicity of the flame-retardant BDE-49 on brain mitochondria and neuronal progenitor striatal cells enhanced by a PTEN-deficient background. Toxicol Sci. 2013 Mar;132(1):196-210.

Naviaux, R.K. A 3-hit metabolic signaling model for the core symptoms of autism spectrum disorder. Mitochondrion. 2025 Nov 14:87:102096.

Naviaux, R.K. Mitochondrial and metabolic features of salugenesis and the healing cycle. Mitochondrion. 2023 May:70:131-163.

Noland, R.C., et al. Carnitine insufficiency caused by aging and overnutrition compromises mitochondrial performance and metabolic control. J Biol Chem. 2009 Aug 21;284(34):22840-52.

Oliveira, G., et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders: a population-based study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005 Mar;47(3):185-9.

Palmieri, L., et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders: cause or effect? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010 Jun-Jul;1797(6-7):1130-7.

Parikh, S. The neurologic manifestations of mitochondrial disease. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2010;16(2):120-8.

Parikh, S., et al. A Modern Approach to the Treatment of Mitochondrial Disease. Current Treatment Options in Neurology. 2009 Nov;11(6):414-30.

Pastural, E., et al. Novel plasma phospholipid biomarkers of autism: mitochondrial dysfunction as a putative causative mechanism. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2009 Oct;81(4):253-64.

Power, R.A., et al. Carnitine revisited: potential use as adjunctive treatment in diabetes. Diabetologia. 2007 Apr;50(4):824-32.

Ramachandran, A., et al. Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity: A mitochondrial perspective. Adv Pharmacol. 2019:85:195-219.

Rector, R.S., et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction precedes insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis and contributes to the natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in an obese rodent model. J Hepatol. 2010 May;52(5):727-36.

Schmidt, Charles W. Mito-Conundrum: Unraveling Environmental Effects on Mitochondria. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2010 July; 118(7).

Scirocco, A., et al. Exposure of Toll-like receptors 4 to bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) impairs human colonic smooth muscle cell function. J Cell Physiol. 2010 May;223(2):442-50.

Shen, W., et al. Protective effects of R-alpha-lipoic acid and acetyl-L-carnitine in MIN6 and isolated rat islet cells chronically exposed to oleic acid. J Cell Biochem. 2008 Jul 1;104(4):1232-43.

Shekhawat, P.S., et al. Spontaneous development of intestinal and colonic atrophy and inflammation in the carnitine-deficient jvs (OCTN2(-/-)) mice. Mol Genet Metab. 2007 Dec;92(4):315-24.

Shoffner, J., et al. Fever Plus Mitochondrial Disease Could Be Risk Factors for Autistic Regression. J Child Neurol. 2010 Apr;25(4):429-34.

Shokolenko, I., et al. Oxidative stress induces degradation of mitochondrial DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009 May; 37(8): 2539–2548.

Sifroni, K.G., et al. Mitochondrial respiratory chain in the colonic mucosal of patients with ulcerative colitis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010 Sep;342(1-2):111-5.

Spindler, M., et al. Coenzyme Q10 effects in neurodegenerative disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:597-610.

Sreekumar, R., et al. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction & diabetes. Indian J Med Res. 2007 Mar;125(3):399-410.

Taurines, R., et al. Expression analyses of the mitochondrial complex I 75-kDa subunit in early onset schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder: increased levels as a potential biomarker for early onset schizophrenia. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 May;19(5):441-8.

Weissman, J.R., et al. Mitochondrial Disease in Autism Spectrum Disorder Patients: A Cohort Analysis. PLoS One. 2008;3(11):e3815.

Zhang, H., et al. Combined R-alpha-lipoic acid and acetyl-L-carnitine exerts efficient preventative effects in a cellular model of Parkinson's disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2010 Jan;14(1-2):215-25.